© 2025 Journey to Coptic Cairo: How the Gatekeepers of Ancient Egypt Continue to Resurrect and Remain. All rights reserved to the authors of this publication.

The term ‘author’ refers to not only the author of this publication but to each and every Copt –– be it priest, monk, gatekeeper, or layman –– that has not only assisted and aided in the making of this publication by way of convening with the archivist during the research trip, being present for interviews, opening closed facilities for the archivist to document or photograph, but to every Copt that has also consistently committed themselves to the Coptic struggle and faith by way of sharing and disseminating Coptic knowledge, histories, and stories.

Author & Photographer: Andrew Riad

With special thanks to:

Hany Shawky, Tasony Febe and Ostaz Tamer in the Monastery of Anba Barsoum, Abouna Kiriakous in the Monastery of Amir Tadros, Nona, my parents, and Teta.

This project and publication is supported by the Graduate Student Engagement Fund at Pratt Institute.

Any views, findings, or conclusions expressed in this publication do not represent those of Pratt Institute.

Archivist’s Note

I will begin here: in the commitment to the Coptic struggle and faith, in the work and dignity, plight and love of the Copts documented in this book, and to every Copt –– past, present, and future –– that I am. This publication, in many ways, is the beginning of what I am sure will be a life-long commitment and struggle in search of truth, of testimony, of faith, and of continuity for and with my people. The Copts are a stubborn people; a faithful people. I employ ‘stubborn’ to mean that we have existed and continue to exist as indigenous peoples on our land for millennia despite our constant erasure and persecution. I employ ‘faithful’ because it is the faith of the Copts –– both in God and in the commitment to our communities and struggle, craft and worship –– that we have remained and continue to remain. This publication is titled Journey to Coptic Cairo: How the Gatekeepers of Ancient Egypt Continue to Resurrect and Remain and it is precisely that, that we continue to do: birthed from Ancient Egypt, we mourn, celebrate, and carry our martyrs, and continue to remain.

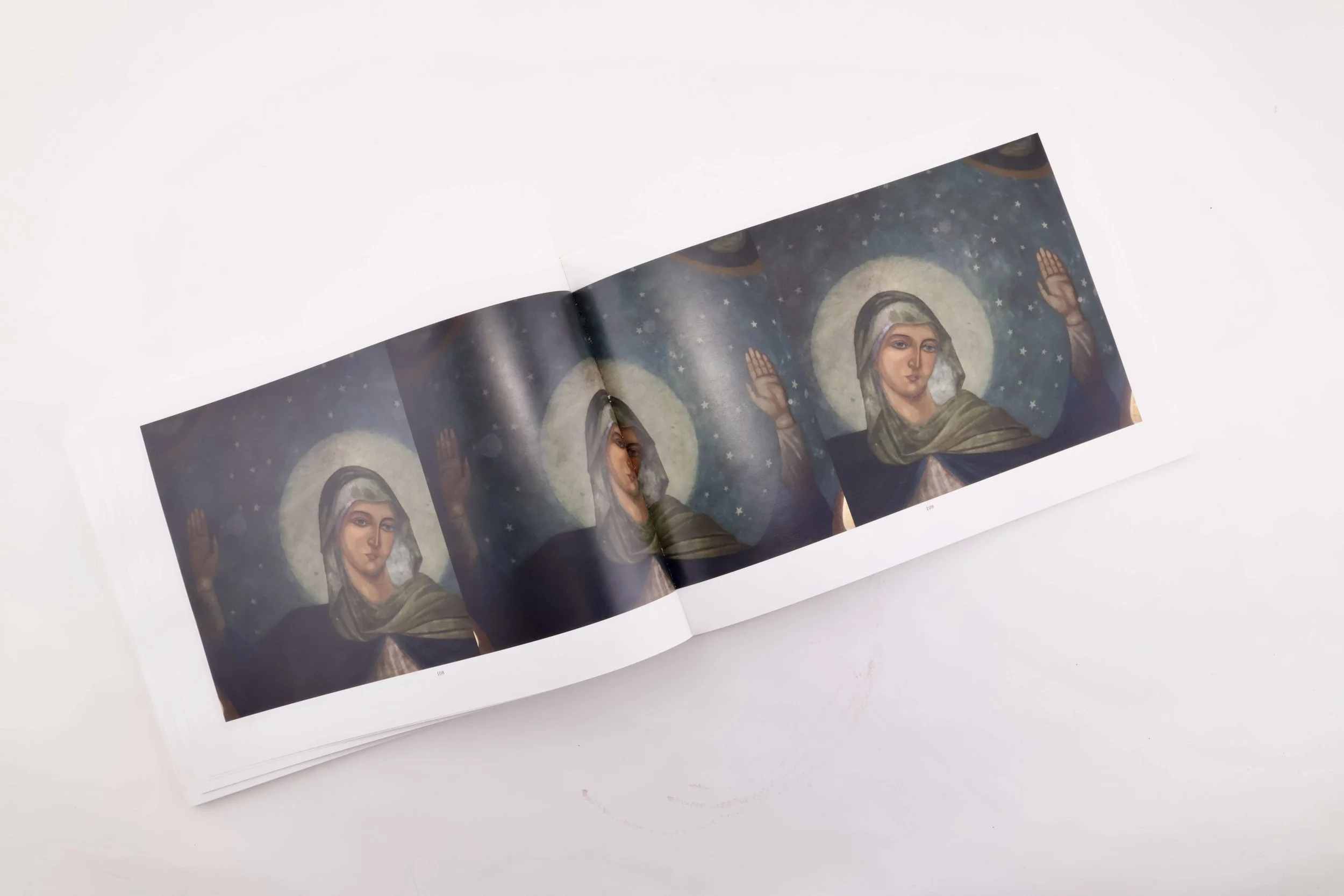

I refer to Copts being the ‘gatekeepers’ of Ancient Egypt because it is fact. The Copts are direct descendants of the Ancient Egyptians. They are an indigenous group that continue millenia-old traditions of crafts and rituals. They speak and pray in a language born from Hieroglyphics and Ancient Greek. Ancient Egypt is laced into every crevice of how we are, from prayer to ritual, food to language: we are living proof of and evidence for. For the record’s sake let it be clear: Ancient Egypt is still alive today, and it is the Copts of Egypt that continue its legacies.

The Copts I refer to in this publication are the Coptic Orthodox Christian Egyptians of Cairo. This publication explores and attempts to document –– and in a sense, archive –– a myriad of historical, biblical, and Coptic sites in Cairo. While an “archive” reduces both the scope and ambitions of this project, I hope if anything, it underscores both the written and oral testimony of history and faith that is Coptic culture, the Coptic Orthodox Christian faith, Coptic art, Coptic architecture, and most critically: records in both writing and the image the Copts of Cairo. This is a sliver of a visual and written record of the spaces and people that make up Coptic Cairo. In other words, it is both an archive and a testament –– a witnessing –– to those that carry millennia of history and faith etched under their right palm and right wrist, under their Coptic cross tattoos. The ambitions of this project are twofold: firstly, it is to provide a record for and highlight Coptic excellence shaping the urban, architectural, and social fabric of Cairo. Secondly, it is to provide a written record to disseminate the truth and history of the Coptic faith and struggle, vested in us by us. The monolith that is history and the fabrication of what is deemed a modern nation-state does not exist in this publication nor is it of any interest to me within the research scope and ambitions of this project. My loyalties –– much like my heart and my faith –– belong to Egypt’s Copts and only to them. I imbue onto this project, as I do with anything I make or write, the legacies and futures of Coptic indigeneity that have come before me and that will come after me and that remain underrepresented, undocumented, and ostracized from a more global (see also: regional, local) dialogue and history. Born out of Ancient Egypt, the Old Egypt, we imbue its legacies into its modernity, carrying with it millenia-old traditions, and by virtue of our faith in God and in our shared struggle, craft, and worship: we have remained and will continue to remain.

Both the scope and ambitions of this project could not have been achieved without the support and guidance of a plethora of people. This project and publication was in part funded by and supported by the Graduate Student Engagement Fund at Pratt Institute. My deepest gratitude is extended to Hany Shawky, who not only guided me and liaised on our excursions and site-visits to various monasteries and churches, but he also vehemently believed in the scope and objective of the project, and he himself has dedicated his life to the struggle and worship, craft and culture of Copticity. I would also like to thank in particular Tasony Febe and Ostaz Tamer from the Monastery of Anba Barsoum, who were kind enough to sit with me for interviews. I would also like to most specially thank Abouna Kiriakous of the Monastery of Amir Tadros, who not only sat with me and discussed the ambitions and history of the monastery, but he was also very kind and loving, and a gifted artist and painter. I, of course, owe my deepest gratitude to those that have raised me through and in the Coptic church, and to those that have taught me what it means to carry the Coptic identity most proudly and honestly, holding it from within my heart inside out: my parents and their mothers, my Nona and Teta. I was fortunate enough to have been able to spend time with my grandmother, Nona, on this research trip and make Hanot with her and her friends. I was also able to visit my Teta at her gravesite for the first time since her ascension to heaven. This project is also for her –– and for every Copt who has ascended to heaven –– may we continue to honor the legacies of your names and the commitment to the Coptic struggle & faith.

As always, and to imbue the beginning of this publication and project with the Coptic spirit, I send you all my Love. محبة. May we all continue to honor and love our shared struggles and plights for continuity, for liberation, and for a more honest and truthful (see: indigenous) world order.

With Love,

Andrew Riad